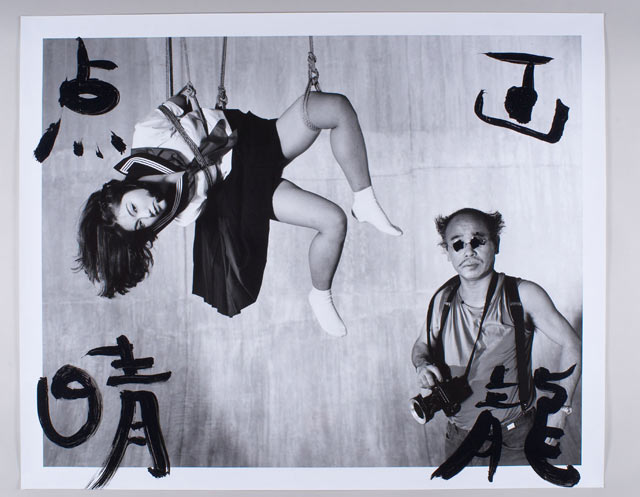

Nobuyoshi Araki is the most famous photographer you’ve probably never heard of. Having published over 450 books, Araki is the second most Googled artist in the world, beating out the likes of Andy Warhol, Picasso and Lichtenstein in sheer volume of searches. His cultural value is immense. So who is this guy anyway, and why should we care? Three words: because art matters. And the stories we choose to tell with our art matter even more, particularly when those stories deal with undertones of abuse, domination and control of a group of people. These stories become part of our cultural undercurrent, a physical reality that none of us can point to directly, but all of us know is there, like air or gravity. And in the process abuse becomes beautiful, domination becomes a creative statement, and control a matter of artistic vision. Let’s look at our friend Nobuyoshi Araki as an example.

I only tie up woman’s body because I know I cannot tie up her heart. ~ Photographer, Nobuyoshi Araki

On that rapey note, you can probably guess that there’s zero chance we’re going to like this guy’s work very much. Nobuyoshi Araki belongs to a school of photographers that uses porn inspired imagery to shock and provoke viewers into thinking they’re looking at deeply profound works of art. Araki’s lot includes sexy-shock photographers like !warning graphic content ahead! Guy Bourdin, Terry Richardson, Steven Klein, and Juergen Teller. By now, tying a naked woman down and/or dominating her to “shock” the viewer is the oldest trick in the photography book, and frankly, we’re over it.

Eroticism in photography (especially fashion photography) is nothing new, it was among the very fist uses of the medium, and often serves to tell important stories about our sexual identity. As such, it’s fairly recently that erotica has (rightfully) been embraced as “serious” art by the creative elite. Art like this can be deeply moving, and completely change the way we see ourselves. And that’s where images like Nobuyoshi Araki’s falls into an ambiguous grey area where the line between smut and masterpiece gets blurry. People look at a bruised and bound woman and call it art because it fills them with a sense of uneasiness, or because it simply turns them on. But by that logic, any crime scene photograph or porno-still would serve as art just as well. So where do we draw the line?

To me an image of an eroticized bound and bruised woman is the visual equivalent of a photograph in which someone is masturbating while dumping oil into the ocean. I get that there’s something socio-political about it which makes it compelling, but that doesn’t distract from the fact that the art itself is deeply fucked, and that the artist himself is kind of a douche for creating it.

Here’s where I want to draw the line, Nobuyoshi Araki’s work does more than merely eroticize the female body, he goes one step further and does violence to it. Araki’s signiature prop is his use of Kinbaku-bi, an ancient form of Japanese bondage which was used on prisoners. The female subjects in his images are painfully tied up, gagged, and dominated like animals. He uses ropes and wires to physically deform their bodies, and depicts them as both physically and emotionally bruised. Of course, the implication is that the exchange between object and subject is consensual, but since images do not speak, and we get no visual sense of context, the uncomfortable situation portrayed in Araki’s photographs could just as easily be interpreted as domestic abuse or rape as consensual bdsm (which is what this is apparently supposed to be).

“Women? Well, they are gods. They will always fascinate me,” explained Araki, “As for rope, I always have it with me. Even when I forget my film, the rope is always in my bag. I only tie up woman’s body because I know I cannot tie up her heart. Only her physical parts can be tied up. Tying up a woman becomes an embrace.”

The interpretation really belongs to the viewer, and there’s no silver lining of pleasure or gladness marking the model’s faces which might dissipate some of the misogynistic undertones of the story within the image. Araki’s photographs fail to tell the story of women’s sexual identity or imply a reason for their binds that goes beyond a male erotic fantasy. If the photos tell any story at all, it is about Nobuyoshi Araki’s frustrated desire for control over the female body.

There is a hands-off attitude about putting any kind of boundaries on art, as if doing so would totally destroy freedom of expression. And to a large extent that’s true. You can’t impose any hard limits on art. But the boundary I’m looking at here is one between a thought-provoking work that inspires contemplation and one that merely serves to perpetuate a culture of violence against women. This is not necessarily a political boundary, but an ethical one. It falls under the same umbrella as kindness and compassion. We’re talking about making a statement, having a vision, telling a compelling story with your art, while also being a pretty decent human being about it. It’s about making art without destroying anything valuable and fragile in the process.

It causes me physical pain to look some of the images above, and I know that sometimes it is the artist’s intention to rouse those kind of emotions in the viewer, but in this case, the artist himself admits that this is not his goal. And what artistic purpose does it serve? In his own words, Araki claims that his goal is to “free [women’s] souls by tying up their bodies.” Artists like Nobuyoshi Araki do not portray their female subjects as complex human beings, but as sex dolls who just happen to be made of flesh and bone.

Women are not gods. They’re people. Treating them as anything other than that is extremely dangerous because it justifies all kinds of irrational biases. Women are not to be worshipped on a pedestal, nor are they to be kicked in the gutter. To me, Araki’s explanation for his award-winning art sounds like your run-of-the-mill madonna-whore complex. So why do people love him so much? What makes him so compelling to the world we live in today?

Nobuyoshi Araki has collaborated with a slew of famous artists and celebrities, most notably Lady Gaga, K-pop superstar G-Dragon, Bjork and polka-dot artist Yayoi Kusama, who all seemed to sincerely love Nobuyoshi Araki’s work. Of course, there’s always a possibility that the artist’s work simply speaks to certain people and not to others, but the art we like is seldom a simple matter of good or bad taste, it’s a matter of social context. Research shows that two things are simultaneously true, the more expose we are to a certain artist, the more we will like his work, and the more we believe that others like his work, the more we will like it as well. In the end, social acceptance and familiarity wins out over taste. And what does it say about our society when images like Nobuyoshi Araki’s can be described as familiar? Commonplace even? It kind of makes your skin crawl.

Why do we continue to laude artists as creative geniuses for merely pornifying the female form in the name of art? Art is a powerful narrative tool, and when there’s so much more that needs to be said about what it means to be human, the struggle for self-actualization and meaning, the fight to be seen for who you are, the search for equality, immortality, eternal youth, the list goes on and on – when you look at it from that perspective, art-work like Nobuyoshi Araki’s feels empty. There are no profound statements. No sense of depth or meaning. Just a passive young woman painfully tied up for the artist’s pleasure. This is not the photographer for our time, and yet, it would be stupid to deny that his particular blend of violence and beauty strikes a cultural nerve given his immense popularity. I think this fact alone says more about where women stand in our society than anything else. What do you think? What role does art play in Nobuyoshi Araki work? Is Nobuyoshi Araki a creative genius or a creative creep?